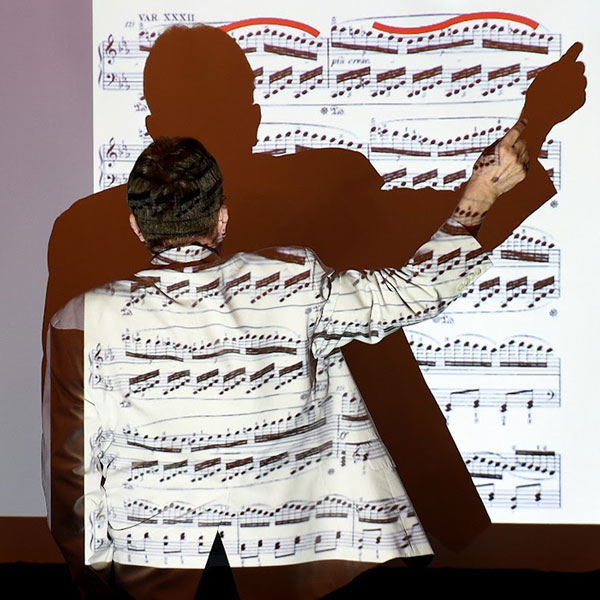

Dr. Stephen Husarik discussing Beethoven's 32 Variations in C minor, WoO 80, at the annual conference of the Humanities Education and Research Association, Chicago, Spring, 2019. Photo credit: John Schmidt

Buried in History: The Musical Discovery of Dr. Stephen Husarik

Written By: Ian Silvester

In an office that could easily be confused for a library by the number of books on

shelves, it was a computer that University of Arkansas – Fort Smith humanities and music history professor Dr. Stephen Husarik pored over seven days a week, 365 days, for nearly

two straight years. Why would a musicologist dedicate so much time to a screen and

not the pages filled with famous composers? The answer came with every keystroke,

as he was unlocking the history of 18,000 musical compositions from 2,400 composers.

In 1834, three years after the death of Archduke Rudolf of Austria, Beethoven’s only composition student, the Archduke’s collection became the centerpiece of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde

Archive collection in Vienna, Austria. However, accessing this collection was no easy

task.

Husarik explained, “A musician who would walk into this library would realize that

it had all of the treasures of European musical culture in the collection,” but access

to it was available only through a card catalog and a catalog of the Archduke’s musical

register. While visiting the Musikfreunde Archive ten years ago, Husarik felt the

pangs of using the archaic system when an idea struck.

“I was looking at all of it and said, ‘You know, I can read this. It’s in German,

French, English, and Italian. I know musical styles, types of genres, and I know the

names of composers. I can just read my way through this, but why don’t they duplicate

it? This should be digitalized.’”

But before Husarik could even dream of committing nearly 1,500 hours to his passion

project – digitizing the musical catalog collection of Archduke Rudolph – the archive

denied him.

Chuckling as he recalled the denial letter, Husarik said he was given a dozen reasons

why, the first three being, “You wouldn’t be able to do this, you shouldn’t try this,

and we won’t let you do this.”

As the project sat on the back burner, Husarik credits the arrival of UAFS Chancellor

Dr. Terisa Riley and her suggestion of researching digital humanities as the spark

that rekindled his attempts. As luck would have it, a change in leadership at the

Musikfreunde Archive was the break Husarik needed to get to work.

From 2021 until May 2023, Husarik was granted access to the archive as he worked to

sort and filter thousands of records which will benefit future scholars. It was through

this process of bringing Archduke Rudolph’s collection into the 21st century that

Husarik’s work reshaped what was previously known.

Sorting through the catalog, something caught his eye, “Now, these 18,000 pieces of

music are supposed to be about people composing at the time of (Joseph) Haydn, Mozart,

and Beethoven only because that’s where the Archduke lived, and what I’m preserving

is the classical era, true Classical music … I was a little surprised, and I’d say,

‘Wait a minute, there’s a woman, I need to jot that down,’” he exclaimed.

Armed with this additional information, Husarik turned his attention to finding who

these women were.

He found 80 female composers in the collection of 2,400, one of whom was Anna Amalia,

duchess of Saxe-Weimar, a composer who predates both Mozart and Beethoven.

Back at UAFS, Husarik solicited music history students to dive deeper into the catalog,

explicitly looking for identifiers of Amalia’s work. Through their collective efforts,

Husarik and his students made a discovery.

“We recovered six pieces that they (Anna Amalia Archive) thought had gotten lost,”

Husarik explained.

The smoking gun was a watermark on the unknown compositions. Husarik traveled to Weimar,

Germany, where Amalia’s library is housed, finding not one but two matching watermarks

to her verified pieces.

“I now know that all six compositions the students found are legitimate; they really

are by her,” Husarik proudly shared.

In the spirit of research, Husarik has shared the discovery and digital access with

fellow scholars and those interested in musical history through numerous presentations,

lectures, and seminars nationwide. Most recently, he presented “Digitally Unpacking

Musical Treasures from Archduke Rudolph’s Musikalien Register” for the Association

for Documentary Editing on June 21, 2023, in Washington, DC.

As Husarik reflects on the project and the findings of UAFS students, he isn’t concerned

with how it will be received in the future but is proud of what it means right now.

“Sometimes we strike it rich in research with luck and hard work,” he said. “I hope

this transcription opens up greater access to all composers of classical music, not

just those with whom we’re familiar.”