Dr. Charles "Chuck" Preston, '72, with a golden eagle in Greater Yellowstone

A Feather in His Cap: The Life and Career of Dr. Charles Preston

Written By: Ian Silvester

It’s rare to make work that reaches millions of people and even more so to build the framework that changes the direction of an entire industry. University of Arkansas – Fort Smith alum Dr. Charles “Chuck” Preston accomplished that and more in the first 40 years of his career in biology and has no plans of slowing down.

Getting His Start

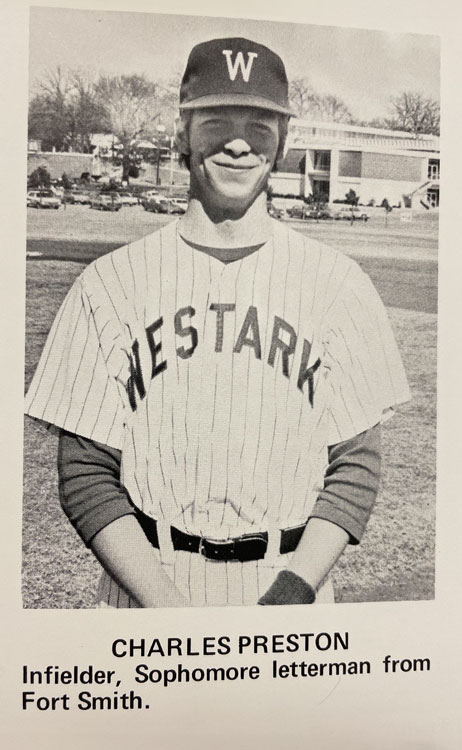

Born in Fort Chaffee, Preston grew up in the area and could often be found hunting

or fishing with his father. He graduated from Northside High School in 1970, and his

ability on the baseball diamond paved the way for him to attend Westark Community

College.

“I was not a great student here, not a bad student, but baseball was the key,” Preston explained.

At Westark Community College, Preston was coached by Bill Crowder and was part of the 1972 team. That season, the team finished with an overall record of 31-18, which included an NJCAA Region II Sub-Regional Championship and runner-up finishes in the Region II Championship and the NJCAA Central District Tournament. The next time UAFS baseball had this deep of a playoff run wasn’t until 2007.

Preston was the first in his family to attend college. Still, despite the challenges of navigating college as a first-generation student-athlete, he found success by leaning into his first love in life: wildlife. Preston had an encounter that changed his life on one of his many trips to the Fort Chaffee area to hunt with his dad.

“I was about seven or eight years old, and my dad and I were driving through the Chaffee reservation when my dad pulled off the road,” Preston recollected. “He said, ‘Look up there,’ and I have these little hand-me-down binoculars, and I was looking up. Sure enough, I finally saw it. It was silhouetted first, and just a little beam of light came through, and I could see this huge, great-horned owl, and his big yellow eyes were looking at me. … We watched it fly off into the darkness, and it made a real impression on me.”

It was the spark that shaped his studies while at Westark Community College. It continued when he played baseball at Arkansas Tech University and earned his bachelor’s degree in biology and wildlife management (1974) and later, his master’s degree (1978) and Ph.D. (1982) in Zoology with an emphasis in ecology, both from the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville.

From Passion to Career

Although Preston’s passion for biology and wildlife translated into academia, a career doing what he loved in the field was fraught with challenges.

After working multiple seasons with the U.S. Forest Service – and meeting Penny, who would become his wife – Preston believed the next natural step with his degree and experience would be working for the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission.

“I went to the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission office in Little Rock, handed in my resume, and said, ‘I’m ready to go to work,’” Preston said. “I handed it to this sweet lady; she opened this huge file drawer and put my resume in the very back. I asked if it was in alphabetical order. She said, ‘No. That’s in order of applications. You’re the last one.’ I asked how many they hire in a year, and she replied, ‘In a good year, we might hire three.’ There were literally 60 to 70 in front of me.”

Not to be disheartened, Preston continued his pursuit of a job in biology. He landed his first museum job at the Arkansas Museum of Science and History in Little Rock, but that, too, wasn’t without its challenges.

There wasn’t a job available, but his charismatic personality won over the museum director. Preston started his career working in museums, cleaning animal cages. While it wasn’t glorious, it did afford him the opportunity to learn how to curate scientific collections and exhibits.

Preston remained at the museum, earning just $500 a month, for two years before beginning

his graduate program at the University of Arkansas. He says it was the “fuel to go

to grad school” after realizing he needed at least a master’s degree to get “somewhere”

in his chosen profession.

But even with a Ph.D., Preston was met a roadblock.

“There was a published paper in one of the scientific journals called ‘Ecology.’ The author had done surveys and argued (for colleges and universities) to not produce as many Ph.Ds. There were roughly 800 graduates in ecology, or some form of ecology, at the Ph.D. level in 1982, and roughly 120 jobs available,” he said with a head shake in disbelief.

Following the setback, Preston followed Penny, an award-winning broadcast reporter, to Little Rock. He was still determined to work in a role deeply connected to biology. He was hired as a visiting assistant professor of biology at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock. After two years, the university created a new tenure-track professorship for Preston. A few years later, he was awarded tenure and promoted to full professor. While at UALR, Preston assisted with creating the wildlife curriculum and served as curator for the university’s small museum.

“It’s one of the first times I was in the position to be on the ground floor of something,” he shared. “I fit very nicely.”

Patience Pays Off

Preston’s UALR tenure concluded in 1989 when he was recruited by the Denver Museum of Natural History, now the Denver Museum of Nature & Science. Leaving his tenured professorship was difficult, but the opportunity to work at a renowned institution in the Rockies was exciting.

By December 1989, Preston moved west to the Mile High City. He was hired as Curator of Ornithology and Chairman of the Department of Zoology.

Preston continued working at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science until the summer of 1998. While in Denver, he honed his craft as a curator and conducted research projects at the 16,000-acre wildlife refuge, the Rocky Mountain Arsenal.

Dr. Ric Peigler, a Professor of Biology at the University of the Incarnate Word who worked under Preston in Denver, eloquently described his work and time at the museum: “(Preston) is a man of the highest integrity and is effective in and passionate about his work with raptor ecology, science education, and conservation.”

Peigler credits his time under Preston with teaching him life lessons that continue to serve him as a professor.

Preston joked that he could have stayed at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science beyond 1998 if he hadn’t answered the call of a lifetime. It was a phone call he almost didn’t take.

“When I got the call, I was leading a field trip in southern Colorado, and this guy said, ‘We’re creating a brand-new natural history museum, and we’d like for you to come interview.’ I asked who is this, and he said the Buffalo Bill Historical Center like I should have known it, and I did not,” Preston said with a laugh.

Housed near Yellowstone, the center housed a world-class art museum, a Plains Indian museum, a firearms museum, and a history museum about Buffalo Bill. However, the center was rebranding to become the Buffalo Bill Center of the West and was searching for someone to create and direct a new addition: a natural history museum.

Former Wyoming senator Alan Simpson was serving as the center’s board chairman and wouldn’t take no for an answer from Preston.

“Simpson and the center’s executive director, Byron Price, called me directly after that and said, ‘We would really like you to come up,’ and he explained a little bit more about what was going on,” Preston said. “They told me I’d create from the ground floor and lead the design and development. How many people have the opportunity to do that?”

Building a Legacy

Preston admitted it was hard to pass up a job when he was so highly sought after. This decision has since defined his career.

He arrived in Cody, Wyoming, with a blank slate and $20 million backing from Nancy-Carroll

Draper, a Center trustee who championed the addition of a natural history museum.

For four years, from 1998 until 2002, Preston worked with architects from Denver and

exhibit designers from Manhattan, New York, to design, create, and fill 50,000 square

feet of museum space. According to the center's website, the result is an “innovative,

informative, and inspiring exhibit experience.”

He arrived in Cody, Wyoming, with a blank slate and $20 million backing from Nancy-Carroll

Draper, a Center trustee who championed the addition of a natural history museum.

For four years, from 1998 until 2002, Preston worked with architects from Denver and

exhibit designers from Manhattan, New York, to design, create, and fill 50,000 square

feet of museum space. According to the center's website, the result is an “innovative,

informative, and inspiring exhibit experience.”

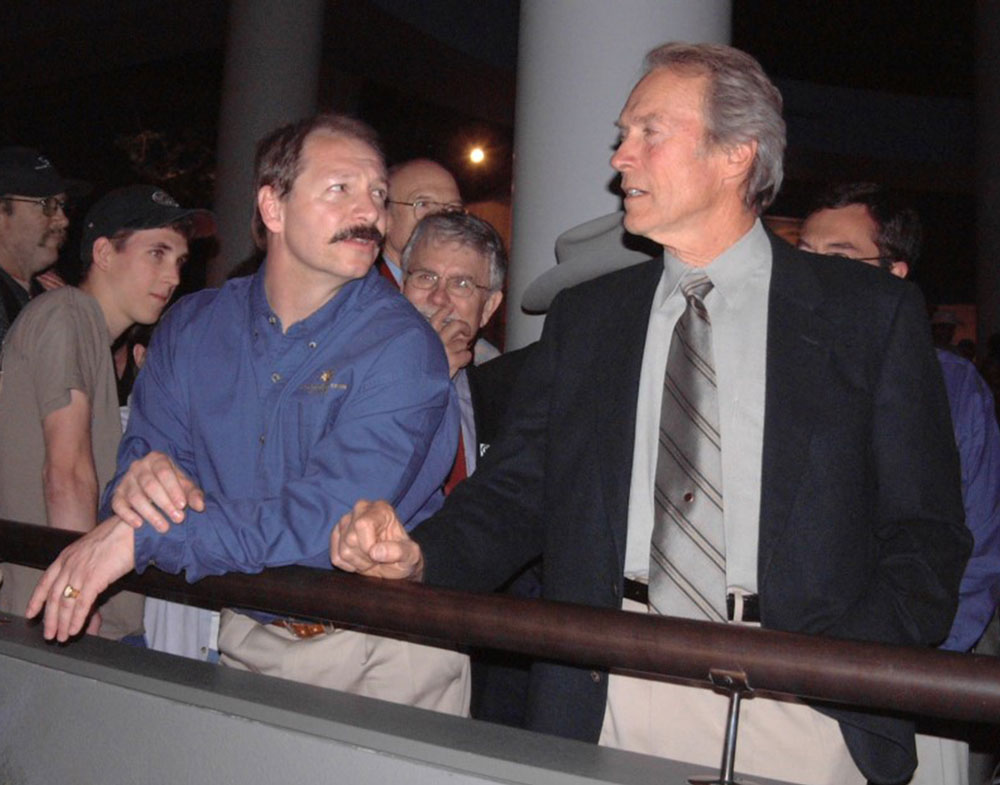

The Draper Natural History Museum opened on June 4, 2002, drawing a crowd that included prominent figures like Richard Leaky, a Kenyan conservationist, and Clint Eastwood. As visitors travel through the museum, they are treated to sights, sounds, and smells that match the area of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem they are touring, from mountains to the plains basin.

“(It’s) considered a model for a whole new genre of natural history museums,” Preston said proudly.

Hired by Preston in 2017 as the assistant curator of the Draper, Corey Anco detailed how Preston “took a risk on a not-yet-built natural history museum” and what it ultimately resulted in.

“It takes a rare combination of ambition, risk calculation, perseverance, work ethic, and gumption to achieve what he did with the Draper,” Anco wrote in an email. “It was (Preston’s) drive to share his knowledge with others in engaging and immersive ways that make the Draper a special, first-of-its-kind natural history museum.”

Anco’s sentiment was seconded by Dr. D. Tim White, a retired Air Force General and former member of the Center’s advisory board who now works as a professor at the University of Maryland.

“The Draper is as experiential as the Guggenheim is immersive. … That was (Preston’s) idea. He pulled it off, not just better than anybody else, but before anybody else.”

Unflappable Passion for Ornithology

Being hired to curate the Draper not only gave Preston international fame in the world

of museums, but it also provided him access to the pristine area, the Greater Yellowstone

Ecosystem. Having direct access to the region, his love of birds, especially raptors,

again came into play.

Preston is one of the world’s best-known researchers of golden eagles. So, what led him to these birds? Preston stated that he came along at the right time with the right ideas.

“Golden eagles became a big concern in the West because of wind turbines and lead poisoning from ammunition. It was coming to the forefront in the fact that some of those populations in the West were declining,” he explained.

After Preston retired from the Draper in 2018, he was named senior curator emeritus and research associate at the Teton Raptor Center. Preston said the golden eagles continue to call him back to Greater Yellowstone. Today, he is in his 16th year of researching the birds and has banded over 100 of them throughout his time in the field.

Dr. Anant Deshwal is an assistant professor of biology at Bradley University and a former student and colleague of Preston’s. Shortly after learning under Preston at the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, Deshwal joined Preston to study golden eagles. He explained that his dream as a student was to work with Preston in the field.

“For Preston, conservation and creating awareness is not a job description. It’s his way of life,” Deshwal said. “I think he’s the only person I know who has the unique ability to conduct research to the highest standards while being able to connect with non-research folks at whatever level they are most comfortable with. … After a feature display, I saw people come up and ask what they needed to do to help. They’re not conservation biologists, but that’s the impact he has.”

An example of Preston’s research can be traced to the harmonious balance between golden eagles and their prey, cottontail rabbits. The equilibrium between the two species populations was apparent, but what he found beyond the surface has proved critical for both animals' survival.

“We monitored nesting success and reproductive rate, assuming that we would get a

baseline after a couple of years. But we discovered that it fluctuated a lot from

year to year. We found that as the cottontail cycle goes up and down, so does the

golden  eagle’s reproduction. … That cycle worked beautifully, and then all of a sudden, when

we expected the eagles to come up after a low, neither rabbits nor eagles came up,”

Preston explained.

eagle’s reproduction. … That cycle worked beautifully, and then all of a sudden, when

we expected the eagles to come up after a low, neither rabbits nor eagles came up,”

Preston explained.

A virus native to Europe had found its way to the Bighorn Basin, hurting both the cottontails and golden eagles. Preston’s research showed that in 2020, the population cycle should have rebounded, but it didn’t.

“Rabbit hemorrhagic disease emerged,” Preston stated. “It really hit our population hard, especially in the Bighorn Basin. … That’s one of the reasons I’m still doing all this—because there are more questions to answer.”

In March 2024, Preston was recognized for his dedication and leadership in biodiversity conservation. He was named the recipient of the Contributions to Biodiversity Science Award given by the University of Wyoming’s Biodiversity Institute and the Buffalo Bill Center of the West. Preston will receive the award during a ceremony on September 13 at the University of Wyoming in Laramie.

No Sign of Slowing Down

Although Preston has eased up in his daily activities, he doesn’t think he will be packing it in anytime soon, even at 71.

“I feel like I could live forever,” Preston joked.

He and Penny have been together for nearly 50 years and currently split their time between Mountainburg, Arkansas, and the Greater Yellowstone area. During the summer months, the pair are back west, Preston researching golden eagles and Penny reporting here and there as a Yellowstone correspondent.

Preston admits his desire for conservation and ecosystem survival is why he will work as long as possible. He believes that humans and animals can live together in harmony. Despite seeing the effects of human greed on the environment, he sees a future where changes are made.

“We have to make some adjustments, but the quality of life is better when we live and coexist with the wild world, not dominate it or try to remove it,” he said.

In the downtime Preston affords himself, he is already working on plans for what’s next. He is in the early stages of developing an Ozark Natural History Museum. Having grown up in Arkansas and spent time between the River Valley, Fayetteville, and Little Rock, he wishes to give back to where he found his passion.

“I give myself one day at a time. I have visions of what I want to do in the future, but I enjoy every day. I don’t take it for granted.”

Media Relations

The UAFS Office of Communications fields all media inquiries for the university. Email Rachel.Putman@uafs.edu for more information.

Send%20an%20EmailRachel Rodemann Putman

- Director of Strategic Communications

- 479-788-7132

- rachel.putman@uafs.edu